A Companion for Owls was a lucky find. I don't read a lot of poetry - I suppose because I think much of it is contrived and superficial. People who can't write decent prose can crank out what sounds like acceptable poetry, much the way people who can't sculpt a believable human hand can spend all day in the barn with a welder and a bunch of old car parts and suddenly they're sculptors.

The premise is that Boone carried with him a little day book and in it he would occasionally write poetry. Simple enough. He was a fairly literate man, and for the day (and his peer group) very well read. It is known that for many years he carried with him a copy of Gulliver's Travels, reading the amazing, almost psychadelic travel tales by who knows how many lonely camp fires. Gulliver's adventures among people small enough to dance in his hand must have seemed in some ways no less strange than the odd juxtaposition of his modernity crashing head long into woodland Indian traditions. I'm sure he often felt as odd and out of place as a man who found himself among a race of super intelligent horses that had developed for themselves language and society and culture.

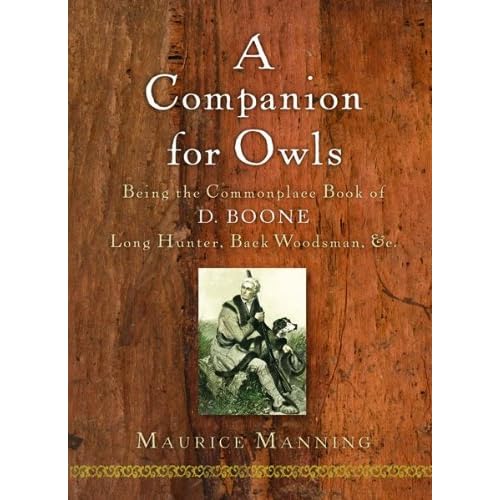

Boone was a man made famous in his own time, something that didn't happen to dozens of his colleagues, many of whom were more successful, smarter, and probably better woodsmen. Boone himself was amazed at his fame and said on more than one occasion, basically, "I don't understand the fuss - others did more and better than me. But whatever." Living a life pock marked by loneliness and loss, and being of a reading bent, it's no great stretch to imagine him writing poetry. And A Companion For Owls is woodsman's poetry - simple, sturdy, sinewy. Dealing with everything from God to getting drunk, to his childhood games with Indians, to his mother speaking to him in Welsh, the pieces meander through his life and work, taking no discernible path, much like he meandered through the mountains, going from salt lick to salt lick, hunting, musing, wandering...would he head back east before winter, or in the spring? Time to decide that tomorrow...or next week.

At its best, this is amazing stuff. His ruminations on the death of his son Israel, on finding his body, "with buzzards maddened at his throat, their wings tipped with his blood..." is powerful. Looking down into Kentucky for the first time, with the hill and valleys laid out before him like a woman's skirts, and so beautiful that his dogs and horses stood mute, is an unforgettable image. Maurice Manning has a woodsman's sense of hunting, of fire, of rifles...sleeping one night he senses a bear snuffling him. He lies still and the bear gently turns him over like a log, looking for insects. He's disgusted with the way that the Indians are treated when William Henry Harrison defeats the last band of Shawnee in 1811and inscribes on a tree: "Old Tippecanoe can goe to hell."

At the end of the volume, he draws a map of heaven, one corner of which is marked with strange crooked X's - this marks the spot "where all old longrifles go to be buried." Hard not to get misty over that.

No comments:

Post a Comment